When Fashion Became Museum Art

Alexander McQueen, Dress, autumn/winter 2010–11. Photograph © Sølve Sundsbø / Art + Commerce

IIn 2011, the landmark retrospective Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty at The Metropolitan Museum of Art proved a turning point for fashion exhibitions. About a hundred ensembles and seventy accessories spanning his career reframed couture as conceptual, provocative, and emotionally charged. Visitors weren’t just looking at dresses; they were witnessing ideas made wearable. More than 661,000 people passed through the Met for Savage Beauty, making it one of the museum’s most attended exhibitions. When the show later travelled to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 2015, it again broke attendance records, cementing fashion exhibitions as blockbuster museum art.

This year, the dialogue between fashion and museums reached a new scale with Louvre Couture, which recently closed after admitting over a million visitors — the second most visited exhibition in the museum’s history after the 2019 Leonardo da Vinci retrospective.

Covering nearly 9,000 square metres, it featured a hundred looks and accessories, drawn from forty-five of fashion’s most emblematic houses and designers, each selected for its intellectual or poetic resonance with the Louvre’s decorative arts. For seven months, the exhibition created a dynamic conversation between contemporary fashion from 1960 to 2025 and centuries of objets d’art, inviting visitors to explore how craftsmanship, ornamentation, and shifting styles connect across time.

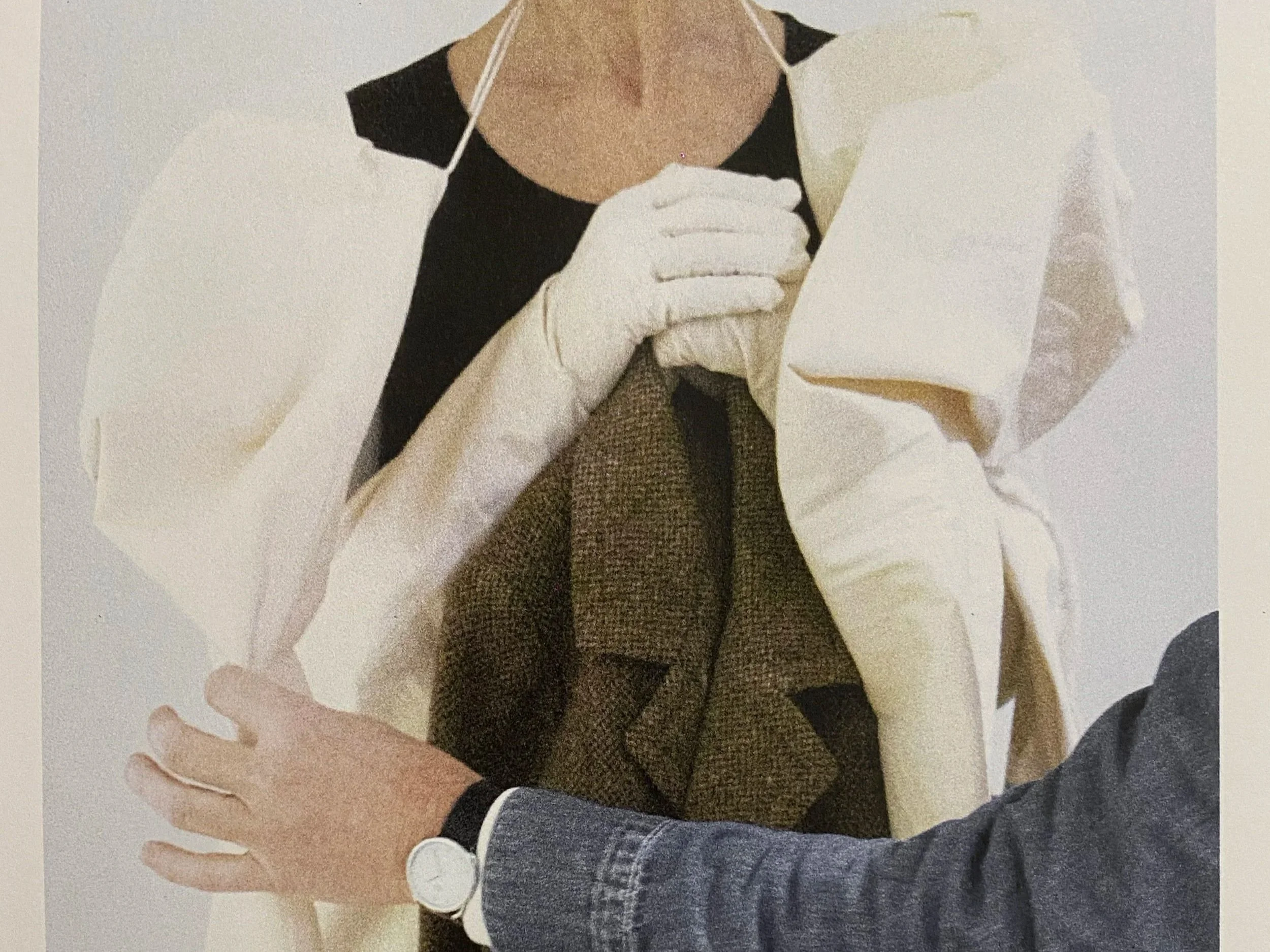

Chanel in Le Louvre setting

Laurence des Cars, President-Director of the Musée du Louvre, reflected on the exhibition’s reach: “Seeing the way their gazes were captivated by a silhouette, then drawn to the Louvre objects around them for a long moment of excitement and surprise — that alone paid the highest of compliments to the Department of Decorative Arts team. I would like to warmly thank the fashion houses and creators who loaned out their collections: none hesitated when we asked them to extend their loan, allowing the public to enjoy the exhibition for a few extra weeks.” Olivier Gabet, Director of the Department of Decorative Arts, orchestrated the exhibition with his conservation team, balancing scholarship and spectacle, a feat the museum hailed as both bold and rigorous.

Between the Met’s Savage Beauty and the Louvre’s recent triumph, fashion exhibitions have shifted from novelty to cultural statement. No longer temporary spectacles, fashion is increasingly woven into the permanent fabric of museums. The Met will soon open a dedicated gallery for its costume collection — a space where garments hang alongside paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts. The V&A in London continues to expand its programming, balancing retrospectives with thematic exhibitions that explore how clothes are displayed, performed, and understood. This isn’t about trend or glamour alone; it’s about craft, history, and context. Museums are making clear that these objects matter beyond the runway.

Exhibition formats are also evolving. Retrospectives of individual designers still draw attention, but there’s now a richer vocabulary. Historical-context exhibitions pair couture with artifacts or artworks to reveal lineage and influence. Meta-exhibitions examine the very idea of fashion presentation — runway culture, photography, staging. Some of the most striking moments come from unexpected juxtapositions.

A John Galliano gown for Dior hangs beside a seventeenth-century Delft vase, the structured tulle contrasting with delicate blue-and-white patterns. A Schiaparelli evening dress hangs beneath a Surrealist painting, its embroidered lobster echoing the canvas above. Smaller works demand scrutiny too. A beaded Iris van Herpen bodice glimmers under the gallery lights; the sculpted shapes and intricate stitching are almost alive in their precision. It’s hard not to marvel at the skill in each fold and thread.

The shift isn’t confined to major fashion capitals. Smaller regional museums are taking risks, curating exhibitions that might have seemed ambitious a decade ago.

The Bowes Museum in County Durham, for example, is scheduled to present a major retrospective of Vivienne Westwood in 2026, while the MuCEM in Marseille is preparing to open Mossi in May 2026.

The exhibition will showcase nearly 150 works by French designer Mossi Traoré, pairing his contemporary garments with the museum’s ethnographic and decorative arts collections. By juxtaposing couture with traditional textiles, craft tools, and everyday cultural artefacts, the show will highlight how fashion functions as both a language and a living cultural practice. These initiatives demonstrate that even outside traditional fashion hubs, regional institutions are embracing fashion as both heritage and art, expanding the vocabulary of what a museum exhibition can be.

Fashion is moving from the ephemeral to the archival. Museums are redefining what is worthy of preservation, what can be interrogated, and what carries meaning beyond style or season. For fashion journalists, the territory is rich: lineage, craftsmanship, cultural dialogue. The runway can still thrill, but the museum asks for reflection. Walking past a layered taffeta skirt or a delicately pleated silk bodice, it’s impossible not to consider the hands that made it, the references woven into it, the work embedded in every fold. Fashion, in these moments, becomes insight.