Art X Fashion at MFIT: When Fashion Stopped Asking Permission

Yves Saint Laurent, dress, off-white, black and red wool jersey, Fall 1965

Is fashion art? The question resurfaces with predictable rhythm — every couture season, every museum blockbuster, every moment a dress commands the same attention as a canvas. But as museums worldwide increasingly position designers alongside painters and sculptors, the debate has shifted from theoretical to practical. We are already treating fashion as a cultural force worthy of gallery walls. The question now is less about permission and more about understanding how these worlds have always spoken to each other.

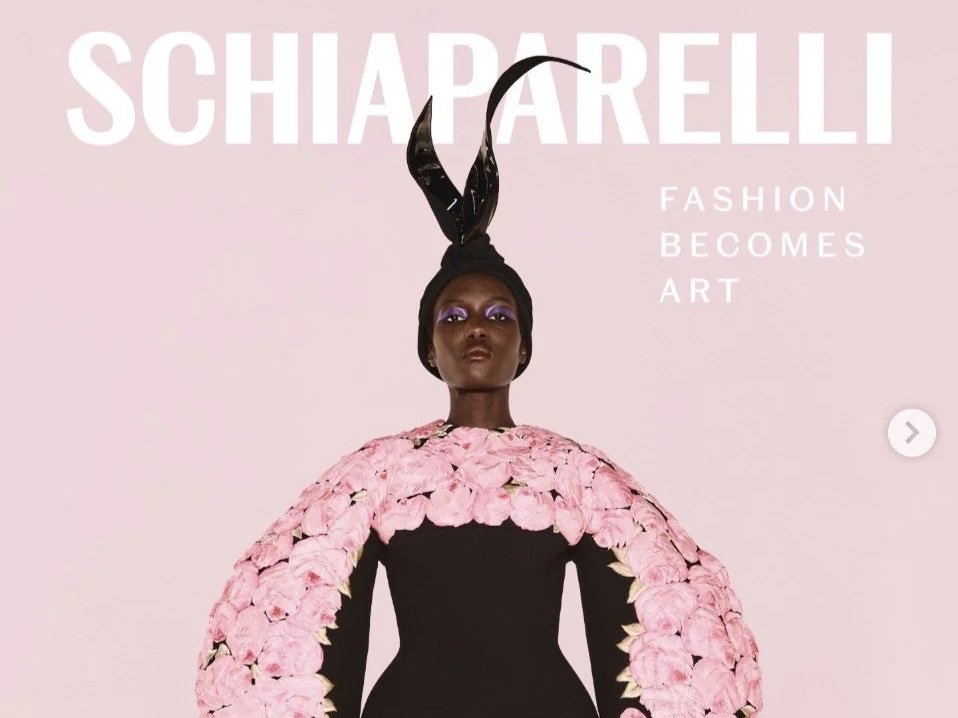

Dr. Elizabeth Way, Curator of Costume and Accessories at the Museum at FIT, knows the question won't settle easily. "It will garner strong opinions and spark lively dialogue," she notes, "but whether you decide that fashion is art or not, fashion's strong and mutual relationship with fine art is undeniable." The exhibition, Art X Fashion, running February 18 – April 19, 2026 at MFIT, doesn't attempt to end the debate. Instead, it sets out to map the territory where the two have met, merged, and transformed each other.

The show will bring together more than 140 pieces — garments, accessories, textiles, photographs, artworks — tracing a dialogue that stretches from Rococo theatrics through Surrealism's unsettling dreamscapes to Pop Art's brazen commercialism. According to the museum, the exhibition is structured around three propositions: innovation as artistry, art as design inspiration, and collaboration as transformation.

The first comes from art and fashion historian Christopher Richards of Brooklyn College, who argues that if fashion demonstrates innovative forms, exquisite craftsmanship, and cultural impact, it qualifies as art. The exhibition will illustrate each pillar through careful selections. Innovation appears in the radical deconstructions of Martin Margiela, Rei Kawakubo's sculptural challenges to the body, and Iris van Herpen's fusion of technology with couture. Craftsmanship finds its champions in Charles Frederick Worth's technical mastery, Paul Poiret's liberated silhouettes, and Elsa Schiaparelli's surrealist wit rendered in fabric. Cultural impact? Christian Dior's New Look and 1970s punk — both seismic shifts in how clothing carries meaning beyond the wearer.

Versace, multicolor cotton and silk jacket, 1991,

The second thread explores how designers have mined art history for visual language. Some approached it with irony — Versace and Moschino weaponising Pop Art to skewer the very consumer culture they inhabited. Others engaged with deeper intent. Grace Wales Bonner, for instance, doesn't simply reference art; she extends its conversations about diaspora, identity, and Black cultural history through her collections. Then there are the translators: Yves Saint Laurent making Mondrian's rigid geometry supple enough to move with a body, Eric Gaskins transforming Franz Kline's gestural abstractions into beadwork that catches light, Christian Francis Roth piecing together Fauvist colour theory into wearable sculpture. These aren't homages. They're reinterpretations that prove fashion can hold complexity.

But it's the section on collaboration that may prove most compelling. The partnership between artist and designer often produces something neither could achieve alone. Louis Vuitton's work with Takashi Murakami and Yayoi Kusama offers a useful case study. When Murakami's candy-coloured monogram prints appeared on Vuitton bags in 2003, the fashion world reacted with skepticism — was this art diluted by commerce, or luxury elevated by contemporary culture? Two decades later, the answer feels clearer: it was both, and that tension was precisely the point. Murakami brought his Pop-inflected examination of kawaii culture and artistic value into direct contact with luxury fashion's mechanisms of desire and status. The result wasn't art made commercial or fashion made artistic — it was a third thing entirely, one that could only exist in that specific collision.

The exhibition will also present partnerships where the relationship runs deeper than a seasonal capsule. Isabel and Ruben Toledo turned collaboration into a life's work, moving fluidly between art, fashion, costume design, and illustration for decades. Their practice suggests that the boundary between disciplines might be more porous than institutional categories admit.

The show acknowledges fashion's historical relationship with artistic identity as well. The 19th-century artist-flâneur understood that clothing could be as deliberate a statement as brushwork. Manet, Degas, Renoir — all used dress to signal modernity, weaving kimonos and medieval references into their self-presentation. That impulse to craft aesthetic identity through clothing hasn't disappeared; it's simply evolved into what we now recognize as "artsy" style, that studied bohemianism that still marks creative professions.

What Art X Fashion proposes to demonstrate across these 140 objects isn't a verdict but a relationship: fashion and art have always shared concerns about form, meaning, cultural memory, and visual impact. They draw from the same wells — history, abstraction, emotion — and both engage the world through objects that carry more than their material weight.

The exhibition doesn't promise to resolve whether fashion deserves the title of art. Instead, Way and her team are offering a framework for understanding how these fields have enriched each other. Whether one sees fashion as art may remain personal. But the kinship between them — that conversation conducted across centuries in fabric, paint, and form — is what the museum is banking on visitors to recognize.

Art X Fashion will run February 18, 2026 - April 19, 2026 at the Museum at FIT.