Vacheron Constantin & Metiers d'art

Metiers d’art are embraced by many watchmaking brands today, but back in the early 1990s, several of these crafts were close to being lost. “Nobody wanted them,” recalls Christian Selmoni, creative director of Vacheron Constantin. “I remember in 1992 we made a few unique pocket watches with a cover in miniature enameling. A well-known Geneva artist needed four months to create just one, and they were fantastic, but we had to carry them on our inventories for years because we couldn’t hardly sell them.” Selmoni says explaining the brand pursued the relationship with the artist because it felt it was its “responsibility to do some kind of patronage for these metiers d’art that were disappearing.”

Fast forward 23 years and metiers d’art are appreciated by watch connoisseurs and therefore much in demand, so much so that several brands, such as Vacheron, have their own in-house atelier.

For Selmoni, the brand’s heritage is an important part of its long-standing support of crafts. After all the very first pocket watches manufactured by Jean-Marc Vacheron in the mid-18th century had their movements adorned with fine engravings.

“Historically we have had four decorative crafts associated with our fine watchmaking: engraving, guilloché, stone-setting, and enameling, a specialty of Geneva dating back to the 17th century when it was a center in Europe for such production,” Selmoni explains, adding, “Even when you go back to the early years of the brand, you can see it has always made a link between the technical traditions of watchmaking and working with decorative parts. We truly have a unique heritage in that field. Through all the files, archives, and sketches — that are luckily intact —we see there is an enormous diversity when we speak about design, not only about the shape, but also in the crafts.”

For these four techniques, Vacheron has in-house craftspeople to work on limited editions or made-to-order commissions, but occasionally it also looks outside for help with crafts it has not mastered. In 2010, it reached out, for example, to a master lacquerer from the House of Zôhiko in Kyoto, to cooperate on a collection that uses the ancient technique of Japanese “maki-e” where sprinkled gold or silver dust on still moist lacquer is used to create the motif.

“This was an interesting project, because we wanted to bring our knowhow in watchmaking, with his know how in lacquering in a true partnership on the dial, so each partner really has 50 percent of the space on these skeleton watches,” Selmoni explains of the Métiers d’Art La Symbolique des Laques collection.

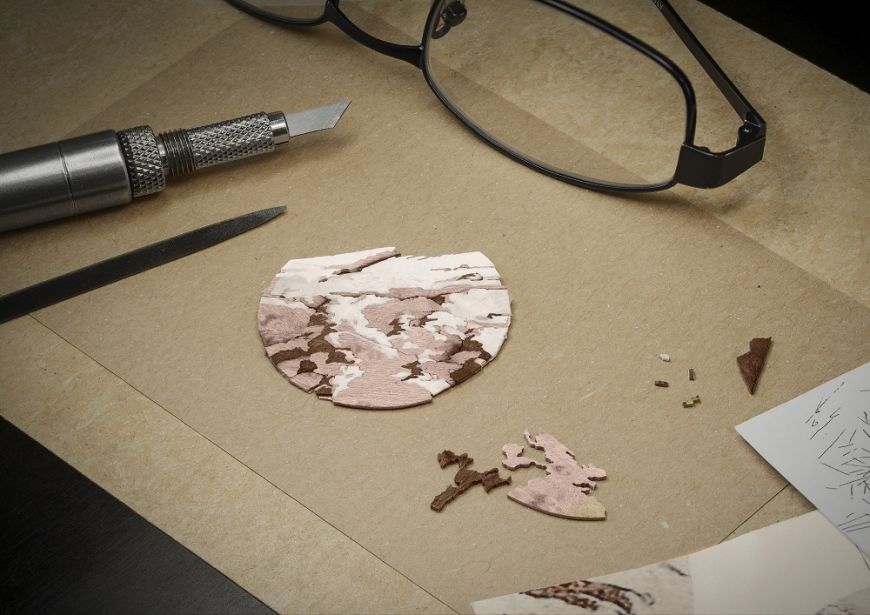

Last year, Vacheron worked with a wood marquetry craftsman, one of only two “masters” in Switzerland, to create two of the dials of its L’Eloge de la Nature collection. In one scene, depicted in pink gold miniature, three wild mustangs prance around a wood marquetry mountain landscape with a snow-capped peak of whitened wood lace-work, while in the other two engraved chamois skip between rocks in a snow scene.

This year, Vacheron remained in-house looking to its engravers for two timepieces with their movements entirely hand-engraved with scrolling motifs and arabesques, reminiscent of the engravings gracing the first pocket watches created by Vacheron Constantin from 1755 onwards.

Selmoni explains this collection was inspired by a 2011 exhibition on the armor of princes of Europe. “I bought the book and it showed how decorated armor and guns were during the 15th century onwards.” he says, adding, “There is no hidden secret really about my inspirations. I try to keep my mind very open, I see things and then we try to see collaboratively with the team how we can adapt this. We’re not trying to ‘harvest’ metiers d’Art, we’re more into incorporating influences.”

Considering other métiers that go in and out of fashion, he says he is content to focus on the four main decorative crafts.

“Frankly it is more challenging to create new concepts incorporating the existing crafts that we have rather than go around to make a media buzz with some unusual crafts that will last for a couple of years. We are very faithful to our roots and our history and it’s a challenge to nurture these crafts and develop them in a very contemporary context. We think it’s better to do this than chase novelties, we really think it’s more important to work deeper with the technique we know,” he says.

Born in the Vallée du Joux and with his grandfather working for Audemars Piguet, it seemed likely Selmoni would work in the industry. Yet it wasn’t an easy path as Selmoni finished college in 1975 right in the middle of the quartz crisis. “It was truly a terrible time. I can still remember many years later the tensions we had at home. Jobwise it was a devastation in the valley. I think we lost 40,000 jobs in watchmaking in a couple of years,” he recalls.

Selmoni studied economics and started working in the financial industry, where he admits he was “quite bored,” until one of his friends asked him in 1990 to join Vacheron Constantin, which at the time had a team of about 80 people. He was put in charge of purchasing and started to learn the business, negotiating with suppliers and developing an interest in how the product was made. In 1996, Selmoni was appointed head of production and planning, which added another facet to what he had quickly learned, and in 2001, he was asked to create the company’s first internal design department and started work on a special collection to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the brand in 2005.

In 2010, Selmoni was promoted to creative director where he now shapes the image of the brand for a future generation. “I’m particularly interested in travel and culture, and I think you can see this in some of our creations, like the Mask collection or the Fabuleux Ornements collection.”

“Couture has its petite mains. Watchmaking has also a long tradition of using craftsmen. The key is to bring these old crafts into the 21st century designs,” he concludes.

As first published in Blouin Lifestyle Magazine