The Stylistic Evolution of Cartier’s Panthers

While most jewelers have embraced representations of flora and fauna in all forms, several houses have over the years become closely associated with specific plants or animals for example, Piaget and roses, Bulgari and snakes, or Van Cleef & Arpels and butterflies. Prowling proudly over Cartier’s bejeweled history, the panther is one of its most famous and enduring motifs, encapsulating 20th-century femininity and style, it is, as Emily Barber, director of the jewelry department at Bonhams, London puts it, “one of the jewelry house’s immediately recognizable symbols.”

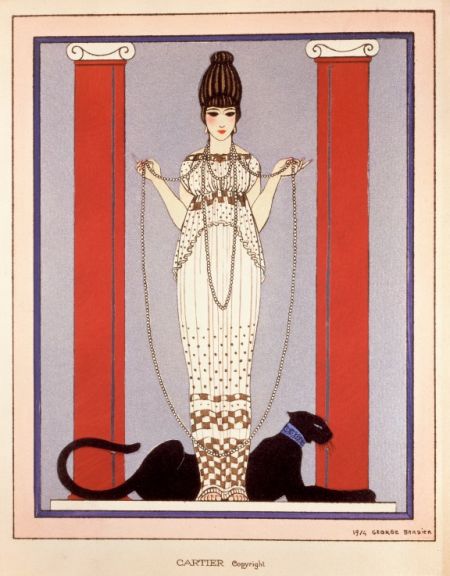

The feisty feline pounced into the house’s history in 1914 when Louis Cartier commissioned George Barbier to paint ‘Lady with Panther,’ a watercolor he planned to use as an invitation to an exhibition to be held in the boutique at Rue de La Paix. This seductive image of a woman elegantly dressed in fashionable Paul Poiret wearing long strings of pearls around her neck and shown with a black panther laying at her feet embraced the infatuation with exoticism of the time, and according to author Hans Nadelhoffer, in his book on Cartier, the bold image also mimicked reality: famed actress Sarah Bernhardt had been reported as having received some of her admirers holding a panther on a leash, while the eccentric Marchesa Luisa Casati had been photographed parading two pet cheetahs on diamond-studded leashes.

That same year, Cartier’s designer Charles Jacqueau would create the jeweler’s first interpretation of a panther on a wristwatch case and bracelet: a stylized version of the feline’s spotted coat, with flecks of black onyx on a bed of pave-set rose-cut diamonds. According to Pierre Rainero, the director of image, style, and heritage at Cartier, the choice to render the pelt this way reflected the fashion for black and white jewelry that the jeweler had popularized in the 1910s with the use of black enamel, lacquer, and onyx in its jewelry creations, particularly as an alternative to mourning jewelry.

The first full representation of the feline — a stalking panther in onyx and diamonds standing between two carved emerald cypress trees — first appears on a Cartier vanity case in 1917. It was a gift from Louis Cartier to his lover, Jeanne Toussaint, whom he had nicknamed La Panthère — a reflection on her independent personality as well as her love for the feline’s skins which could be found in her eclectically decorated flat.

Impressed by her charismatic personality and exotic sense of style, Cartier gave her a job in late 1917 or early 1918 putting her in charge of Cartier’s accessories department, and under his mentorship, she would play an increasingly important role at the jewelry house to eventually become its creative director of jewelry in 1933.

Supported by the talented designer Peter Lemarchand, who had joined Cartier in 1927, she elevated the panther to an iconic status, reigning supreme over the firm’s jewelry bestiary.

In 1935, she conceived a collection of yellow gold jewelry with several panthers, including the first panther ring with two heads facing each other. “I think these were very much in the spirit of antique jewelry, like the jewels that were found in the tomb of Philip de Macedon. Sadly, we only have photos of those pieces, no actual pieces, and I would love to find some if they still exist,” Rainero says.

Toussaint’s interest in panthers might have remained a footnote in the Cartier archives if not for the Duchess of Windsor. In 1948, the Duke of Windsor commissioned a brooch with a fierce-looking three-dimensional yellow gold panther with black enamel spots, set stretched over a 90-carat emerald cabochon. The following year, the couple bought a second panther brooch that had the animal, set in diamonds with sapphire cabochons as spots, proudly standing atop a 152.35-carat Kashmir sapphire cabochon — Cartier re-acquired that piece at Sotheby’s Geneva in 1987 for $933,000, paying seven times its estimate.

"That second piece was not a special commission, but something from our stock and that’s very important because it had been seen in our boutique window and photographed. The first piece had gone straight from our atelier to the Duke and had only really been seen by the friends of the couple. After the duchess bought the [second] piece, the interest for the panther never stopped; it’s almost something that bothered Jeanne [Toussaint], because its success went well beyond what she had expected, and I guess she was annoyed that all that customers now wanted was panther, panther, while there were so many more offerings,” Rainero notes.

The Duchess of Windsor bought several other big-cat jewelry pieces including, in 1952, a diamond and onyx bracelet with an articulated body that can perfectly embrace the wrist. That piece was last sold at Sotheby’s auction in 2010 for £4,521,250, well above its £1.5 million estimate and set a new record for the highest auction price for a piece by Cartier.

An arbiter of taste in society, the Duchess’s interest in the panther was quickly followed on both sides of the Atlantic. The heiress Daisy Fellowes, who was editor of Harper’s Bazaar in Paris, commissioned a diamond-and-sapphire panther brooch. Other famous panther devotees over the years have included the actress María Félix, known as “the Mexican panther,” and Princess Nina Aga Khan, who accumulated a collection of Cartier’s panther pieces ranging from a jabot-pin to a gold fluted bracelet with panther heads that could be worn as earrings but also transformed into a handle for a Cartier evening bag.

Rainero points out there has been a clear evolution in the stylistic iconography of the Cartier panther. “The one from 1949 was extremely ferocious with yellow diamond eyes, canines in platinum, and she stands in a very dominating position over the stone. Some say that it represented the way the Duchess saw her position in social circles, affirming herself,” he notes, adding that while many of these earlier panthers were ferocious looking, the designs in the ‘60s, with their bigger eyes, gave the panther a softer, “almost tamed” appearance.

Rainero explains that a later fundamental technical change led the panther iconography in a new direction. “Until the middle of the ‘70s, the panthers were entirely made by hand. Whether in gold or platinum, the metal was worked by hand and that meant that the initial intention would be subjected to the difficulty in working the metal — it was just very difficult to create a very expressive panther. But in the mid-70s it was decided to move to casting. The design would first be sculpted in wax and then a metal cast would be done, before being set with all the stones. So the panther moved from being a reflection of the work of the jeweler to that of the wax sculptor piloted by the designer’s drawing,” Rainero explains, adding there were internal arguments over this move which had sprung from a desire to create a more expressive panther.

“The decision helped evolve the style of the panther, and by the ‘80s we had returned to a very naturalistic design,” he adds.

In the 1990s, young panthers appear in Cartier’s repertoire, which again opened the doors for a new design approach. “The cub has a very different approach with the stone. With an adult panther you would have her walk on the tree and the stone would be a fruit, but the cub can naturally play with the stone like a toy, and that allows for very interesting creations,” Rainero explains.

He notes that customers attracted to cubs often have quite different personalities than those who prefer the adult panthers. “With the baby it’s more about cuteness, femininity, while the adult panther is more about independence, fierceness.”

In the last 10 years, the rendering of the panther has evolved further. Rainero points out that the jeweler has appropriated the animal so completely that its designers feel they can be more experimental with its representation, for example fragmenting its body to create certain abstract effects or elongating it body to create a necklace.

The panther has also been rendered using new techniques and materials, such as marquetry of wood and straw, gold granulation, and most recently 3D stone mosaic. “As we work with different métiers d’art, it’s interesting to use the panther as an exercise in style,” Rainero says.