The Arlésienne Gets Her Museum

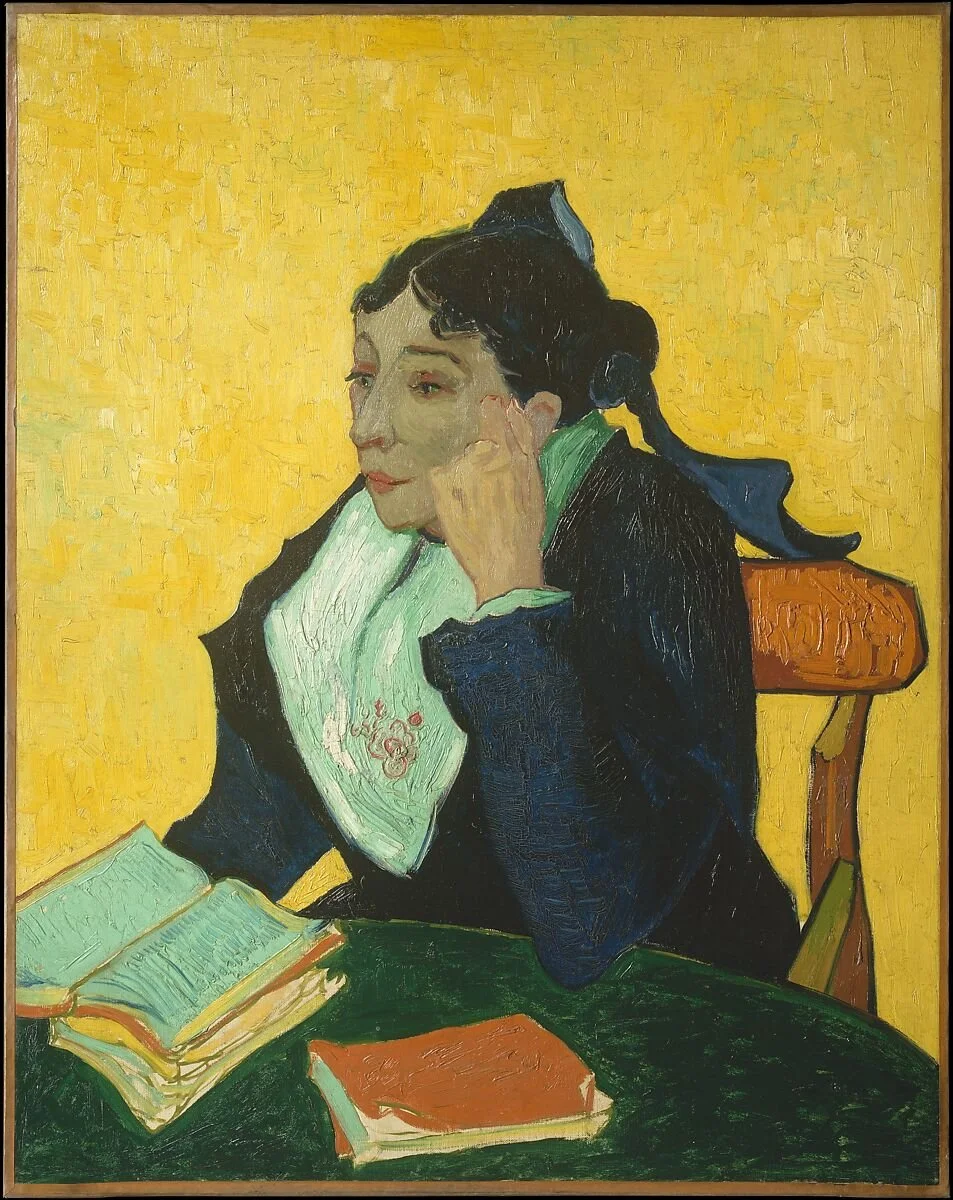

The Arlésienne, with her brocaded silk, delicate lace, and towering coiffe, has always lived more in imagination than in reality. Van Gogh painted her, Bizet immortalised her in music, and and for over a century she has graced postcards as the ultimate Provençal icon. Yet behind this enduring fantasy lies something far more fascinating: a way of dressing so precise it communicated status, occasion, and identity. Earlier this year, the House of Fragonard opened the Musée de la Mode et du Costume in Arles, finally giving these garments emblematic of Provençal identity the stage they deserved.

In the 1820s, an Arlésienne's costume was carefully structured to convey meaning. Towering coiffes were secured with narrow black ribbons bordered in silk velvet. Long gold "filleuse" earrings fell to the shoulders, while Maltese crosses hung from velvet ribbon chokers above black silk corsages trimmed in handmade lace. Even the arrangement of a fichu – the small pleated kerchief crossed over the chest – communicated social information: marital status, village of origin, or whether the wearer was dressed for church or the market. Parisian fashion filtered south and evolved into something entirely local, creating a system of dress as precise and codified as any court protocol.

The new museum exists thanks to two women devoted to preserving this visual language. Hélène Costa grew up in wartime Cannes near the Marché Forville, where young people danced in traditional costume during curfews – a subtle act of cultural defiance. Decades later, when interest in Provençal dress revived in the 1980s, she began hunting forgotten textiles, building a collection focused on pristine colours and rare motifs. Meanwhile, in Arles, Magali Pascal was assembling her own archive of Arlésienne costume. Named Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 2010, she and her daughter Odile (a former ceremonial Queen of Arles) documented these garments with scholarly precision, reconstructing complete ensembles across social classes.

When the Costa sisters acquired Pascal's collection in 2019, shortly before Magali's death, two complementary visions came together. On view in Arles today, the exhibition demonstrates how individual pieces gain meaning in dialogue.

A circa 1770 robe à la française in silk damask hangs near an 1835 velvet coiffe ribbon, while a cotton cape from 1785, its fabric chintzed to a high gloss, sits alongside the elaborate jewellery that would have completed a formal ensemble in the early 1800s. One particularly moving display recreates a costume from around 1820, based on a miniature ivory portrait attributed to Michel-Philibert Genod. Curators matched the painting’s details to surviving pieces: the coiffe shape, the exact filleuse earrings, and the arrangement of lace and ribbon. Separately, these were fragments; together, they show how a woman actually dressed for a specific moment.

Studio KO, the architects behind Marrakech’s Yves Saint Laurent Museum, has renovated the 17th-century Hôtel Bouchaud de Bussy to house the collection. A modern staircase provides access to the upper floors, while interiors incorporate Provençal references, including glossy floors inspired by Marseille faïence and neutral-coloured walls. A gilded brass door, designed like a piece of jewellery, opens onto exhibition spaces. Charles Fréger's video installation features nine contemporary women performing the complex rituals of Arlésienne dressing, their backlit silhouettes showing just how choreographed this daily practice once was.

What makes this museum compelling is its refusal to treat these garments as picturesque relics. Each piece communicates meaning, signalling social standing, marital status, and identity through its design and details. The Arlésienne may have been mythologised into abstraction, but in these rooms she becomes specific again – and far more interesting for it. For anyone visiting Provence, the museum is an invitation: to step into the streets of Arles as they once were and see how style, society, and tradition were woven together in silk, lace, and ribbon.